The Pedagogy of Bimi Boo

The pedagogy of Bimi Boo is a comprehensive approach to the early development of children aged 2 to 5 years.

Theoretical foundations of the approach

The child is the central object of Bimi Boo pedagogy. In our understanding, the child is seen as a protagonist; we endow him in advance with the ability and interest in exploring the surrounding world. This resonates with the approach to children in Reggio Emilia pedagogy. The child as protagonist, according to Reggio Emilia’s founder, Malaguzzi, is viewed as “rich in potential, strong, powerful, and competent” (Malaguzzi, 1993, p. 10). We agree with this point of view, integrating it into our philosophy and drawing inspiration from it in outlining our guiding principles. The approach of Maria Montessori (Montessori, 1967) also places the child at the center, emphasizing the importance of freedom of choice in activities and gaining knowledge through individual practical experience. Thus, the Bimi Boo approach is child-centered. This means that we are also focused on the importance of each child’s personal and social development and well-being.

There’s no doubt that the age range of 2 to 5 years is a time of great opportunity. Numerous studies show that it’s a period during which children rapidly develop the basic abilities that form the foundation for further positive probabilities of high achievements in academic studies in school years (Duncan, Dowsett, Claessens, Magnuson, Huston, Klebanov, & Japel, 2007). This applies to cognitive functions, behavior, social, emotional, and self-regulation abilities, as well as physical development (Institute of Medicine, 2000; Richter, Daelmans, Lombardi, Heymann, López Boo, Behrman, & Bhutta, 2012).

The importance of play in early childhood cannot be overstated, as there is a significant body of scientific data supporting its role in various development areas. This data underscores the necessity for parents and educators to prioritize play as a central component of development and learning approaches for preschoolers. Piaget (Piaget, 1962) asserts that play is crucial for cognitive development. Through play, children experiment, make discoveries, and learn about the surrounding world. According to Vygotsky (Vygotsky, 1967), play is necessary for social development, allowing children to refine communication skills, understand the nuances of social norms, and learn interaction with peers and adults.

The environment in which Bimi Boo pedagogy works is predominantly the home setting and the child’s familiar surroundings. We strive to relieve parents of the need to adhere to complex rules for properly organizing the environment, making all our products have potential we call Ready-to-learn. In practice, this means that Bimi Boo’s product can be provided to the child as is — install and launch the app, turn on media content, or give a toy without a complex game instruction and without mandatory adult assistance.

Furthermore, digital products can be actively used by the child not only at home. For example, parents often give gadgets to children when they need to wait in line or when the child is on the road. In the last two cases, the “useless” time, from the perspective of the inability to organize a directed and manageable educational process, is filled with learning possibilities.

This concept is defined as a range of educational opportunities and experiences that can potentially support and enhance the development and learning outcomes of young children. Learning possibilities can include both structured and unstructured activities, integrating learning into play, and creating an environment that facilitates learning and development. Often, the search for learning opportunities involves exploring the characteristics and hidden potential of a certain environment, primarily the natural environment (for example, in The Ngahere Project by Kelly, Sacker, Del Bono, Francesconi, & Marmot, 2013). Instead, we propose to find opportunities not in a special space but in time, offering children simple and always available applications and media content.

Black et al. (Black, Walker, Fernald, Andersen, DiGirolamo, Lu,… & Grantham-McGregor, 2017) presented their “Life course conceptual framework of early childhood development,” according to which early childhood development requires nurturing care defined as health, nutrition, security, and safety, responsive caregiving, and early learning, provided by parents and supported by the environment. In this context, Bimi Boo pedagogy is ready to become part of this environment, creating tools and space for realizing the rich innate potential of every child.

The importance of the home environment is clear—it definitely influences what a child can learn, his or her expectations and attitudes, and his or her attitude toward others during the early years (Institute of Medicine, 2000:389). Hereinafter, we adopt the acronym HLE (home-learning environment), infusing it with the meaning of a quality home environment filled with materials and tools that support early learning as part of the “responsive caregiving” approach. Bimi Boo pedagogy exists so that parents have more opportunities to provide their children with a more stimulating HLE.

The availability of relevant learning materials in the home environment supports children’s language skills and reading skills (according to Purcell-Gates, 1996; Sénéchal, LeFevre, Thomas, & Daley, 1998; Tabors & Snow, 2001). Research has confirmed the relationship between the presence in the home environment of certain types of toys for symbolic play (such as cooking sets) and toys for fine motor skills (such as blocks) and the early development of a child’s language skills (Tomopoulos, Dreyer, Tamis-LeMonda, Flynn, Rovira, Tineo, & Mendelsohn, 2006), as well as intrinsic motivation to learn (Gottfried, Fleming, & Gottfried, 1998).

Among our products, digital products, i.e., those that are played (reproduced) on digital equipment (ICT equipment — tablets, televisions, smartphones, computers) available in families, hold special significance. Nowadays, numerous studies show that the use of smartphones, televisions, and other digital devices by preschool-age children is very significant and continues to grow. For example, a study by Kabali, Irigoyen, Nunez-Davis, Budacki, Mohanty, Leister, and Bonner (2015) showed that children as young as 2 years old use some device daily and spend a comparable amount of screen time engaging with televisions and mobile devices.

Bimi Boo Company does not abandon traditional pedagogy and methods of education; it is necessary to read to children, tell stories, sing, play with household items, and use complex speech. At the same time, the company looks forward to a radically changed world, providing free educational children’s games and software (with science fiction and a fictional world in them) in practical applications. The online pedagogical methodology of Bimi Boo is positive for early development because children are motivated to independently use the built-in opportunities for game-based learning on gadgets, the number of which is steadily growing. The latter cannot be denied.

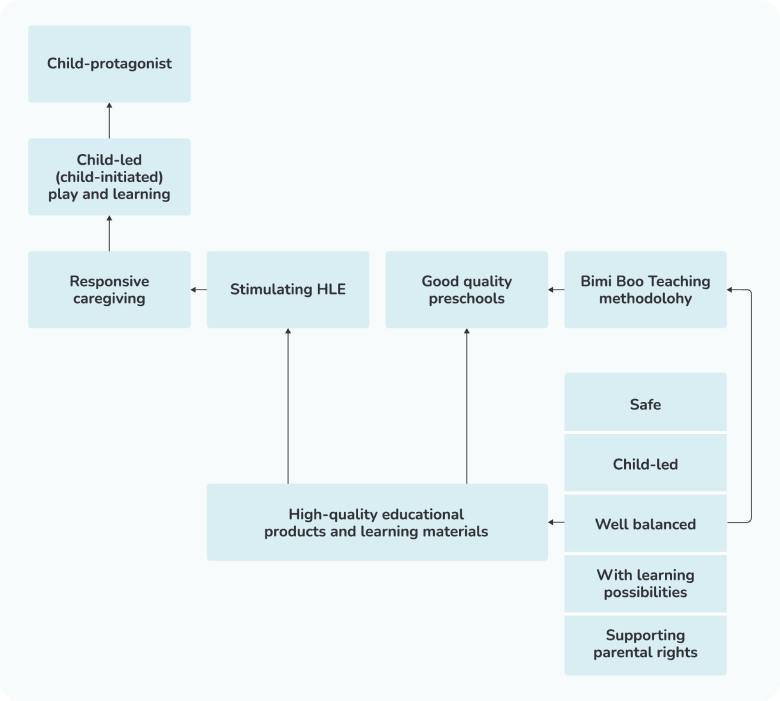

Summarizing all of the above, we come to the following conceptual framework, which underpins our approach: The child protagonist, endowed with innate potential and interest in play and learning, takes a proactive stance. Based on this, we believe that the most optimal type of educational play activity for a child aged 2 to 5 years is child-led (child-initiated) play and learning. It is through child-led play and learning that the child gains an invaluable foundation for further achievements, including success in academic learning. Parents need to heed current recommendations from reputable organizations and educational researchers regarding appropriate amounts of screen time for young children.

We hope that the products we are developing at Bimi Boo in the context mentioned above can become an indispensable part of a quality and stimulating HLE, as well as being used as play and educational materials in educational institutions.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework of the Bimi Boo pedagogy.

To meet our stated goal, all Bimi Boo products are designed according to our guiding principles, detailed below.

| Principle | Meaning |

| Safety | Safety is the top priority for all our products. We firmly believe that all products (including digital content), methods, and tools designed for use by children must not contain any potentially harmful or dangerous elements. |

| Child-Led Learning | The pedagogy of Bimi Boo is inspired by the concept of child-led learning. The idea of giving children more freedom and initiative is far from new and has a multitude of compelling arguments to its credit. For instance, the study by Vaisarova & Reynolds (2022) suggests that spending on average more than 60% of learning time on child-initiated activities can contribute to improving school readiness among three- and four-year-old preschoolers. We define child-led (child-initiated) play and learning as a single activity where play is inseparable from learning, and learning is inseparable from play. |

| Balance | When creating our products, we strive to achieve a balance in the following contexts:

|

| Learning Opportunities | An important practical mission that we, as creators, set for all Bimi Boo products is the continuous search for and effective use of so-called “learning opportunities.” By this, we mean potential types of activities that can contribute to children’s learning and development. Because most of our products are primarily intended for use in a home environment, a feature of the sought-after opportunities is that they must be deeply, yet subtly, integrated into a child’s everyday life. |

| Parental Rights | The capacity of children to absorb moral messages from media products, such as cartoons or television shows, is not fully understood but is presumably assessed as moderate (Hardy & Calaborne, 2007). Some moral messages, for example, can be attributed to “universal human morality” (social morality, the morality of fairness). Such moral messages are usually considered positive and are found universally in all stories, cartoons, fairy tales, and other products created for the child audience, and Bimi Boo’s products are no exception in this regard. A completely different type of moral message, in our view, are those that can be associated with any hidden or explicit religious and political motives. We are convinced that the choice of political and religious position is exclusively the responsibility of parents and guardians. Thus, we have no moral right to transmit messages of this kind through our products. |

Table 1. Guiding principles of the Bimi Boo pedagogy.

Discover Bimi Boo Pedagogy!

To view the complete document “Bimi Boo Pedagogy”, you can download the PDF file

Reference list

- Black, M. M., Walker, S. P., Fernald, L. C. H., Andersen, C. T., DiGirolamo, A. M., Lu, C. & Grantham-McGregor, S. (2017). Early childhood development coming of age: science through the life course. Lancet, 389(10064), 77-90.

- Duncan, G. J., Dowsett, C. J., Claessens, A., Magnuson, K., Huston, A. C., Klebanov, P., & Japel, C. (2007). School readiness and later achievement. Developmental Psychology, 43(6), 1428-1446.

- Gottfried, A. E., Fleming, J. S., & Gottfried, A. W. (1998). Role of cognitively stimulating home environment in children’s academic intrinsic motivation: A longitudinal study. Child Development, 69(5), 1448–1460.

- Hardy, B., & Claborne, C. (2007). Encyclopedia of children & adolescents and the media. Sage.

- Institute of Medicine. (2000). From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early childhood development. National Academy Press.

- Kabali, H. K., Irigoyen M. M., Nunez-Davis, R., Budacki, J. G., Mohanty S. H., Leister, K. P., Bonner, R. L. Jr. Exposure and Use of Mobile Media Devices by Young Children. Pediatrics. 2015 Dec;136(6):1044-50.

- Kelly, J., Sacker, A., Del Bono, E., Francesconi, M., & Marmot, M. (2013). The Ngahere Project: Exploring the dynamics of child development and early learning in natural environments. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 11(3), 234-247.

- Malaguzzi, L. (1993). For an education based on relationships. Young Children, 49(1), 9-12.

- Montessori, M. (1967). The discovery of the child. Ballantine Books.

- Piaget, J. (1962). Play, dreams and imitation in childhood. Norton.

- Purcell-Gates, V. (1996). Stories, Coupons, and the TV-Guide: Relationship between Home Literacy Experiences and Emergent Literacy Knowledge. Reading Research Quarterly, 31, 406-428.

- Richter, L. M., Daelmans, B., Lombardi, J., Heymann, J., López Boo, F., Behrman, J. R., … & Bhutta, Z. A. (2012). Investing in the foundation of sustainable development: Pathways to scale up for early childhood development. Lancet, 389(10064), 103-118.

- Sénéchal, M., Lefevre, J., Thomas, E., Daley, K. (1998). Differential Effects of Home Literacy Experiences on the Development of Oral and Written Language. Reading Research Quarterly. 33. 96-116.

- Tabors, P. O., & Snow, C. E. (2001). Young bilingual children and early literacy development. In S. B. Neuman, & D. K. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook for early literacy research (159-178). New York: Guilford.

- Tomopoulos, S., Dreyer, B. P., Tamis-LeMonda, C., Flynn, V., Rovira, I., Tineo, W., Mendelsohn, A. L. Books, toys, parent-child interaction, and development in young Latino children. Ambul Pediatr. 2006 Mar-Apr;6(2):72-8.

- Vaisarova, J. & Reynolds, A. (2022). Is more child-initiated always better? Exploring relations between child-initiated instruction and preschoolers’ school readiness. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability. 34. 1-32.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1967). Play and its role in the mental development of the child. Soviet Psychology.